Picture this: you’ve just had your safety strategy development workshop. You’re reminiscing about the great ideas that were brainstormed, the positive initiatives that were created and the high-fives echoing left, right and centre.

You even thought up some catchy slogans like ‘Safely does it’ and established a new set of core values like ‘care’ and ‘trust’.

The new safety strategy has been born and people are pumped.

Brilliant. This is it. You’re going to win the hearts and minds of the workers and create a step-change improvement to workplace health and safety.

—

Fast forward a few months and the latest survey you’ve asked people to respond to shows little improvement. Or maybe nobody bothers to respond at all.

Maybe you haven’t done a survey, but incidents are still cropping up and the criticisms and grumblings are still being heard through the grapevine.

Now you’re thinking ‘what is wrong with these people?’

It can be really deflating when something you genuinely pour your heart into doesn’t work. Now, this is not a criticism. Having the passion and desire and demonstrating a real care for others should be highly commended.

The execution is where the mistake is made.

There’s a key ingredient missing. That key ingredient is the input from the people who are most affected by safety – those on the frontline; the implementers of the strategy.

And by input we don’t mean you asked a few people who showed an interest to take a quick survey.

We mean a real feeling of equal contribution, that this is something they’ve ‘got their hands dirty’ with and co-created.

Who should be involved in your safety strategy development and why?

Studies show that ‘low-power actors’ such as frontline employees are often ignored and excluded due to an error in our thinking process called the ‘just world fallacy’.

Ever heard someone say something like ‘what goes around comes around’, or ‘everything happens for a reason’?

These figures of speech are manifestations of this cognitive bias that often trick us into believing that if something good (or bad) happens to someone, it’s just deserved and served by some kind of cosmic justice.

In social psychology, this bias leads to the phenomena of victim blaming.

In organisational psychology, it leads us to favour the input of those in higher roles, as we assume they are more competent.

Overcoming this bias is the key principle of open strategy formulation, which advocates for a higher degree of internal inclusivity and participation beyond the top management team and influential middle managers.

Research suggests that frontline employees are important to the formulation process, as they generate ideas that are practically relevant and critical to new knowledge creation.

‘Human capital’ is a key source of competitive advantage and the tacit knowledge (practical skills, ‘street smarts’) they hold is a key strategic asset – so use it!

This goes for both internal employees as well as contractors – they can play a critical role in creating strategy ideas. This is particularly relevant given the growing contractor workforce (‘gig economy’) we have seen occurring across many safety-critical industries.

Read about the growing ‘gig economy’ and more WHS trends here.

More organisations are shifting from an internally ‘closed’ process of strategy formulation centred around top management team, towards an ‘open’ process measured on the dimensions of transparency and inclusiveness.

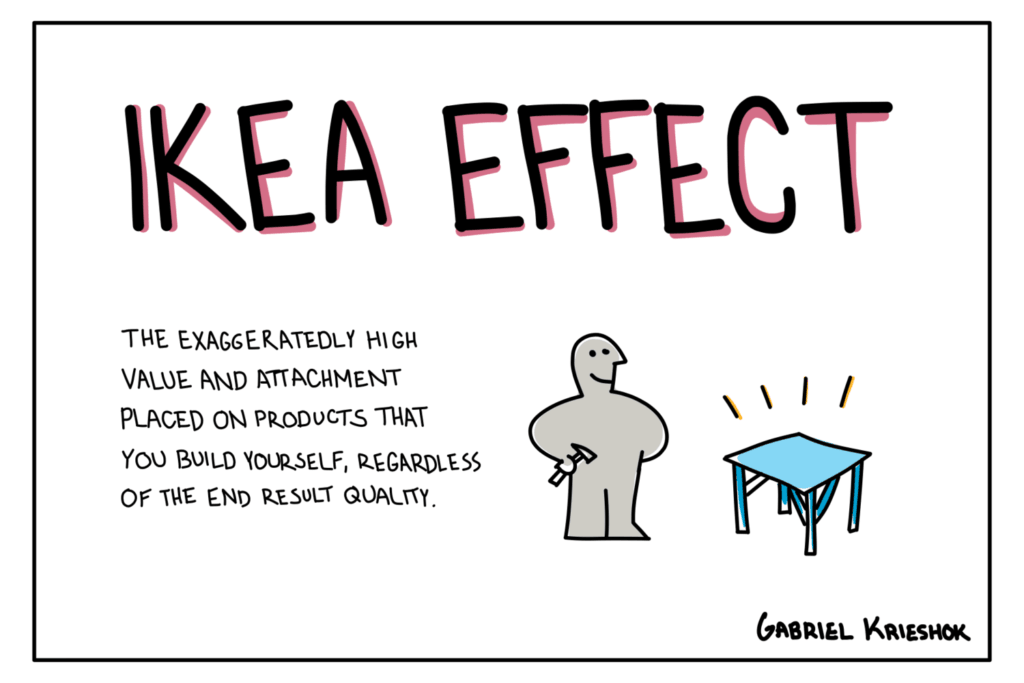

Ever heard of the ‘Ikea effect’? Yes, it’s a thing.

This is another cognitive bias that happens when people construct something themselves. Even if they do a godawful job, they value the end result more because they played a part in its creation.

Related to other biases like the ‘endowment effect’ and ‘effort heuristic’, the Ikea effect applies to safety strategy development – the builders of the strategy will value it, defend it, and implement it. So include the frontline in safety strategy development as much as you can because they will give you great ideas, and will take pride in implementing their hard work!

What are the risks of too much input?

Some key risks for an ‘open’ safety strategy development process include:

- An unwillingness of stakeholders to participate

- Groupthink

- Cost of creating availability for frontline worker participation

- Stakeholder disappointment with the process

Overcoming these risks and reaping the benefits of an open safety strategy development can be a mammoth task. Stay positive and stay tuned for ‘Successful Safety Strategy Development – Part 2: The What’.